SAKE: AN INTRODUCTION

Laura on 16 Jun 2017

By Angela Mount

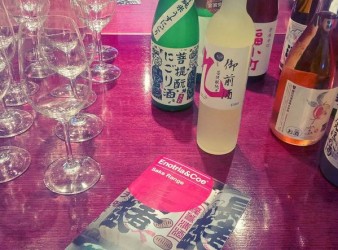

I’ve written, talked about, and judged wine for more years than I care to remember, but last week, I went back to school – Sake school to be exact. With an extensive range of this specialist Japanese rice wine hitting the shelves at Great Western Wine, I decided it was time to re-learn how to differentiate between my Futsu-shu and my Daiginjo.

Sake, in its simplest terminology is an alcoholic beverage made from rice, water, yeast and a mould called Koji. Its history and long heritage puts the traditional wine industry in the shade – forget 13th century Tuscan dynasties, sake breweries date back over 2000 years. There are now over 1200 breweries across Japan, most of them still following centuries-old traditions, and many of them still tiny family-owned businesses.

Sake wasn’t really on my radar until a couple of years ago, when, as a Panel Chair at the International Wine Challenge, I witnessed the scale of the IWC Sake, which was running alongside; 1300 Sakes, 60 judges, a mix of Japanese and non-Japanese experts from all over the world, including a team from the Sake Samurai Association, a junior council of the Sake Brewers Association, which is in charge of the IWC project, and who are doing a great job at promoting Sake in new ways.

Chris Ashton, Director of the International Sake Challenge told me “We do what we always do; we provide the platform for sakes to be judged objectively. We advise, we help. Japan does the rest. And they do an amazing job by using these awards to promote rural and lesser-known areas. In Fukushima in 2015, the Champion Sake was used as part of the re-generation of the whole area after the nuclear disaster. Fukushima was back on a world stage for its products. The Governor used it to promote the region. The brewer met the Japanese Prime Minister and his sake was given to the G7 leaders as a gift. Everyone benefitted”. This is now happening all over the country, and increasingly, internationally. The Wine & Spirit Education Trust’s accredited Sake courses are proving increasingly popular, and specific Sake lists are popping up on restaurant lists all over London and now, beyond.

To the layman (me), the process of making Sake seemed extraordinarily complicated, the descriptions and classifications even more so. The only way I managed to learn was by going back to basics and equating the classifications, as much as I could, to my more familiar wine territory. Comparing blended whisky with single malt is probably another good way of referencing the complexities and intricacies of this increasingly popular drink.

For wine enthusiasts reading this, think about Bordeaux classifications – we start with Bordeaux, then we move up to Bordeaux Superieur, then to maybe Medoc, and finally to Pauillac. If you apply a similar principle to Sake, it makes understanding the subject a whole lot easier.

In the simplest of terms, a Futshu-su Sake is entry level, likely to be volume scale. Move up a level and you’ll get to Junmai or Junmai Ginjo; explore further up the scale and you’ll reach the more rarified heights of Junmai Daiginjo.

Just like wine, the terroir where the rice is grown (the best quality rice, Yamadanishiki comes from Hyogo), plays a significant part, as does the quality of the water, and the difference between ordinary ‘table’ rice and premium ‘sake’ rice. However, the crucial element in the sake process is the milling, or ‘polishing’. The more the rice is milled, or polished to remove the fats and proteins on the outer layers, the purer the quality of the remaining starch, and therefore the higher the quality of the resulting sake. Once again, drawing a vinous analogy, to help understand the process, it’s like wine yields, or even better the process of making sweet botrytised wines, where shrivelled grapes are picked in tiny quantities. The more the grain of rice is polished, the smaller it gets, making production more costly, and volume often tiny.

Just like wine, the terroir where the rice is grown (the best quality rice, Yamadanishiki comes from Hyogo), plays a significant part, as does the quality of the water, and the difference between ordinary ‘table’ rice and premium ‘sake’ rice. However, the crucial element in the sake process is the milling, or ‘polishing’. The more the rice is milled, or polished to remove the fats and proteins on the outer layers, the purer the quality of the remaining starch, and therefore the higher the quality of the resulting sake. Once again, drawing a vinous analogy, to help understand the process, it’s like wine yields, or even better the process of making sweet botrytised wines, where shrivelled grapes are picked in tiny quantities. The more the grain of rice is polished, the smaller it gets, making production more costly, and volume often tiny.

I’ve never really been a Sake fan, probably because I didn’t understand it; I love sushi, but until now, I’d always opt for a glass of aromatic wine and wouldn’t even nod a glance at the Sake list. Last week’s tasting was a revelation, made even better by the fact that Ollie, one of the Great Western Wine team, married to a Japanese wife and having lived in Japan for many years, set himself the task of matching Sake with cheese – I love a challenge. Anyone, who thinks that all Sake tastes the same, please reconsider. Just like wine, the variety, style, aromas and flavours transcended all levels of the taste profile scale. Most Sakes are between 13 and 16% alcohol, and have complex flavours, with that indescribable, almost impalpable ‘umami’ element, which simply adds to the enigmatic perception of the wines. Unlike wine, they can be enjoyed cold, or warm, although the higher grades are normally served chilled.

Sake is graded based on a polishing ratio, known as Seimai-buai, which refers to the percentage of the rice remaining after milling. We started with a Futsushu, which has an average 70% grade. 1.Gozenshu Futsushu Ancient Mountain, Tsuji Honten from Okayama is run by the 7th generation of the family brewers, who still use an ancient, medieval brewing technique. On the nose I smelt wild herbs, and a rich, almost oaty aroma, with hints of mushrooms. It tasted creamy, rich, again with a toasted oat edge, yet freshened by a herbal twist. This worked surprisingly well with the sweet and salty taste and texture of cheddar cheese, and by its nature, would be an interesting match to wild mushroom risotto.

We then moved on to Junmai, a rich, full-bodied style of sake – for novices, the easiest way of explaining this, is that it’s a bit like comparing Muscadet with Chardonnay, if we revert to the safety net of wine. Staying with the Tsuji Honten brewer, they also produce 2.Gozenshu Junmai Bodaimoto Nigori Misty Mountain, a delicious, creamy, gentle sake, and one of my favourites. Soft, and silky, with scents of guava and mango, it’s textured, with a distinctive coconut edge, but with a citrus tang and spice on the finish; it’s also a cloudy sake. Try this one with sweeter, spicy, soy-influenced dishes, it was a star with blue cheese.

3.Fukukomachi Junmai Karakuchi Evening Sky, Kimura Shuzo. Established in 1615 by the family of a high-ranking Samurai and situated in the Akita prefecture, the brewery is located by a spring of pure mountain water. I enjoyed the freshness and liveliness of this sake, with its crisp, green apple and fenugreek notes, with a hint of warm liquorice and a creamy edge. It worked well with the creaminess of a brie-style cheese, and is a great sushi match.

Staying with the Junmai style, the tasting then moved to 4.Shirayuki Edo Genroku Redux, Konishi Shuzo, which has just won a silver medal at the IWC Sake awards. This is the oldest sake brewery owned and managed by the same family, founded in 1550. It’s old style sake, fermented in wooden barrels, and with a low polish ratio of 88%. Dark, rich and intense, this really did have the umami factor, with its nutty, dried fig and soy character – try this one with dark chocolate, may sound strange, but it really worked.

Moving up the grading scale, we moved to Ginjo, a higher grade of polish (minimum 60%), producing spicy, aromatic styles of sake. Konishi Shuzo also produce 5.Konishi Silver Ginjo Hiyashibori, one of my favourites from the tasting, with a nose of fresh lime, fennel and liquorice. Vibrant, citrusy and lifted, it has fresh acidity, and brightness (think dry Riesling as a comparison). I’d definitely be happy with this one to accompany oysters, sashimi and tempura prawns.

Continuing the journey, Daiginjo, is a high grade sake, milled to a minimum of 50%. 6.Fukukomachi Daiginjo Hidden Glade, Kimura Shuzo. This was rich, aromatic and subtly perfumed, with an elegance of flavour and texture. Very fruity and vibrant, it combined an interesting mix of bright citrus and peach fruit, with deeper, warm spice, cedar, and cinnamon notes. The umami effect, and the mix of sweetness and saltiness made it work well with tangy pecorino cheese, and would be great with highly-spiced Asian seafood.

Finally onto a couple of fruit-infused sakes. 7.Gozenshu 9 Yuzushu, Tsuji Honten is a lip-smackingly fresh, lemon-stashed sake, made from the Japanese fruit yuzu, which is a citrus cross between lemon, orange and grapefruit, and Junmai sake. I loved this – bright, breezy, and vivid, with an incredible freshness of citrus flavours – concentrated and delicious, with more than a hint of lemon meringue pie. Move over Limoncello, this is the new kid on the block; and at a mere 9% alcohol, it’s refreshingly light in alcohol too.

8.Kodakara Nanko Umeshu, Tatenokawa Shuzo was the last sake on the list, a top notch, deliciously sweet, yet fresh sake made from sweet nanko plums, steeped in Junmai Daiginjo sake. It’s utterly delicious, and reminds me of plum and almond tart, with scents and flavours of frangipane, toasted almonds, and plum compote, lifted by a citrus edge. Irresistible, and a perfect alternative to dessert wine. It’s certainly on my radar.

The whole subject of sake can be quite daunting and difficult to understand, as I’ve learnt; but it’s fascinating and worth exploring, in all its guises. If you’re reading this, and interested in learning a bit more, why not sign up for a WSET accredited sake course. Marie Cheong-Thong is a passionate advocate and runs regular courses in London (www.thelarderat36.co.uk). “Sake, once a very quirky traditional Japanese drink, is now spreading rapidly worldwide. Even here in the UK, from just a handful of brands 10 years’ ago, there are now hundreds of different sake lines widely available — today, you can even buy sake at your local supermarket”, she told me.

Sake is still a relatively little-known product, and off the mainstream, but based on my initial foray into the subject, well worth exploring.