Decoding a wine label

Laura on 1 Jun 2015

Wine labels are meant to provide all the information you need to understand what you are buying; however, what they often do is just confuse, and add to the dilemma of what to choose. With hundreds of wines on most supermarket and wine merchants’ shelves, it’s often an impossible maze, and the labels might as well be written in foreign languages (which they often are, but that’s a different story).

Every label you see looks different, and seems to send out different messages. Quite simply, there’s no set rule. Let’s forget the pretty or whacky pictures, and actual design, what should wine labels be telling us, and how can we understand them?

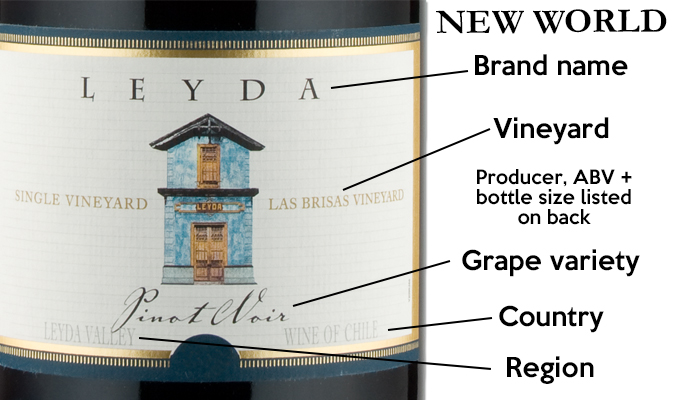

Explanation of labels tend to split into 2 camps, and it really depends on whether you like choosing your wine by region or grape variety – the New World wine regions (basically everything that isn’t Europe) showcase the grape variety first; European wines tend to focus on the area, or region first, and don’t always mention the grape variety, although more and more are jumping on the ‘grape variety first’ bandwagon, as it makes everything a lot easier. Unless you know your Saumur-Champigny from your Savennieres, it’s a bit of a minefield understanding the style of wine in the bottle, with the very obvious exceptions of wines such as Chablis and Rioja.

So, what’s an easy way to decode the basics?

The legal stuff – every bottle of wine needs to provide the following:

- country of origin, ie where it’s from

- alcoholic strength – written in % either on front or back of bottle

- Vintage – some wines are a blend of vintages, however most will have a vintage (year) on them, so you can tell how young, or mature they are

- NV – used on Champagnes and sparkling wines - the majority of fizzes are a blend of vintages, and offer a consistency of style. Sparkling wines from a single vintage, will detail that specific vintage.

- Volume – 75cl, 1.5lt etc.

- Name and address of the bottler – this is a useful tip, especially with supermarket wines; if the wine has been bottled at source ( ie where it was made), you’ll see the name and address of the producer. If it’s a wine that’s been shipped in bulk , and bottled in the Uk, there will be a series of letters and numbers after the words ‘imported and bottled by…’

- Quality designation – what does this mean? Well it varies from country to country, which doesn’t make things easier, but it’s a legal system, especially stringent in Europe. For French wines, you may see ‘Vin de Pays’, or ‘AC’, or other; In Italy, ‘DOC’, DOCG’, ‘Vino da Tavola’. Confusing in themselves, and impossible to explain in one simple piece, but they are linked to regional and legal legislation about which styles of wine can be produced, in which region, from which grapes…. I know, not easy; whilst it’s easy to assume that DOCG wines from Italy ( including the very best of Barolo, Chianti Classico etc), would be the best, some of the most outstanding, expensive and prized Italian wines are simple Vino da Tavola, because the producer has decided to use grape varieties that aren’t approved in that region. Confused? Most people are..

So after that, it’s all about the useful information, that’s going to tell you that little bit more: Back labels are well worth reading, as this is where you’ll usually find the information about the style of the wine ( dry, sweet, full-bodied), tasting notes and often, food pairing ideas.

One of my biggest gripes is the number of wines on the shelves that have back labels in foreign languages – hardly the way to inform the potential buyer. I realise it’s difficult for small producers to print labels in different languages, but it’s gobbledeegook to most people, and makes it even more important to make the front label send out some clear information – it also makes it crucial for wine merchants to provide their own information about the wine on signage near to the wine.

I’m also a harsh critic of wine back labels which are over complicated and use terms and language that are just not relevant to most people and hardly recommend a wine – after all, would you want to buy a wine that has hints of creosote and freshly cut twigs?

The useful stuff:

Grape variety – not legally required, but probably the most important part of the label – this will tell you what the wine is made from and from there, you’ll know what style of wine it is – from Sauvignon blanc to Syrah. This is the normal way of labeling in all New World countries, and increasingly in Europe. However, in some, more traditional, and legislatively-bound regions, including Bordeaux, and Chianti, the grape variety is not mentioned on the front label.

Region – this explains in more detail where the wine comes from, for example Cotes du Rhone, Stellenbosch, or Western Australia. The more detail there is, the more specific the area where the wine is produced – a bit like zooming in on a google map – for example, Awatere Valley, Marlborough, New Zealand. This pinpoints in more and more detail where the wine is made.

District or vineyard – generally, the more detailed the description is, the smaller the area, from which the wine was produced. Let’s use the example of Domaine Gilles Robin, Crozes Hermitage, Rhone, Le Papillon 2013. In simple translation, this means that within the Rhone Valley wine region, there’s an area called Crozes Hermitage. There’s a domaine ( estate) called or owned by Gilles Robin; he makes many wines, but this particular wine is called ‘le Papillon’. So lots of producers make several different wines on their own properties but will call them by different names, or by the name of the individual vineyard where the grapes were grown.

Brand name – the name of the producer or the brand – for example Elki (the brand name of a range of wines produced in the Elqui valley in Chile), or Marques de Riscal ( the name of a top producer in Rioja)

Some other terms to understand – these are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg, but should give some guidance

Estate bottled – this means that the wine was produced and bottled on the estate, where it was grown – rather than going into a bigger blend.

Sans barrique – this means ‘unoaked’ – a term increasingly used on bottles of Chardonnay for those of you who don’t like oaky wines

Vieilles Vignes – literally translated as ‘old vines’ – means that the wine has been produced from older vines, which, if carefully handled, produce the best wines.

Crianza – used on Spanish wines, means the wine has been aged in oak; Crianza Reserva simply means that it has been aged in oak, and also in bottle for longer ( specified requirements)

Riserva – used on Italian wines – again this relates to the amount of time that a wine has been aged both in barrel and in bottle.

Classico – as in ‘Chianti Classico’ – this means the wine is from a more specific and top quality smaller district within the Chianti region.

Chateau or Domaine – In France, this means that the wine was produced was one single estate , or patch of land – fiefdom in another word.

Premier Cru, or Grand Cru – more legal wording, used in France, mainly in Champagne and Burgundy – this normally denotes a smaller, more specific area within a region ( ie Chablis Premier Cru), which has been legally and formally identified as producing generally higher quality fruit, with lower yields.

This is just the tip of the iceberg, but I hope these key tips help explain some of the key terms that you’ll see on wine labels. If in doubt, read the back label ( if it’s in English), trust your instincts, or don’t be afraid to ask.

By Angela Mount